What's Wrong with Human Rights?

As we all

know there has been much heated discussion about rights, and it has been

particularly fierce in the transgender battles. Much of the focus there has

been on men who have transitioned and their right to be treated as women. If

recognised, this right means they can, for example, compete in women’s sports

and occupy women’s safe spaces. However, in criticising aggressive transgenderism,

more often than not the wrong culprits are fingered and the reason the whole

thing has got out of hand is overlooked.

First, the

culprits. People have always said and demanded daft things, and the internet

has only exacerbated this phenomenon. But, traditionally, if a lobby group

demanded something the majority felt was outrageous, they would simply be

ignored. Or, if their demands were directed at government, told their request

had been taken under advisement and they would be informed of the outcome in

due course. The heart of the problem with the demands made by transgender activists

– and those of many other vocal rights groups − is not the fact that people

make these demands: it’s that they are listened to, and that policy is developed

and enforced accordingly. The culprits are our governing bodies.

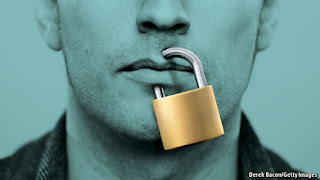

The same

goes for the de-platforming of speakers with ‘divergent’ views at universities,

literary festivals and just plain paid-up speaking venues. One might expect an

outcry in social media and perhaps even on-the-street protests, but it is the authorities

who listen, who cave in to demands and who de-platform speakers that are

the culprits. If going ahead with an event creates a risk to public safety, then

arrest those threatening public safety. Don’t deny the right to free speech

under cover of preventing hate speech, with ‘hate speech’ defined as anything that

someone, somewhere, objects to. It seems obvious, but both sides in this fight are

utterly intransigent.

Why has this

happened? Why do our governing bodies listen to the rights-driven demands of

vocal lobby groups? It’s easy to accuse certain political and social classes –

not to mention certain media outlets – of being irretrievably woke, but why has

that happened? The question is complex, but one often-overlooked part of

the answer lies in the notion of rights as the basis of moral

decision-making and, by extension, legislation. If a group states that it has a

certain right and proclaims that this right must

be respected, our guardians simply don’t know what to do. They are lost. They

lack a moral compass.

Modern rights-based

thinking derives from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was

proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948. The

Declaration set out “for the first time, fundamental

human rights to be universally protected”, and it was hugely influential. The

EU is rights based, as is clear from its official website:

“The European Union is based on a strong commitment

to promoting and protecting human rights ... Human rights are at the heart of

EU relations with other countries and regions”. EU policy includes “promoting

the rights of women, children, minorities and displaced persons”.

Rights-based moral thinking was an understandable

reaction to the horrors of the Second World War, and the Declaration sprang

from noble intentions. But,

as with many good intentions, these have had perverse and unintended outcomes. A clue lies in that last sentence of the EU statement relating to minorities.

The original idea was that minority groups would be included in universal

human rights, “rights that

are inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality,

ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status”. The perverse outcome is

that any minority group whatsoever sees itself, by virtue of being a minority

group, as having special rights.

This presumption

of special rights results in the demand for special privileges, which is most

apparent in intersectionalist arguments. If I belong to a certain minority

group, I am allowed to use words that you are not allowed to use. I can call

you racist but I can never be racist. I can call you transphobic or

Islamophobic, but you can’t call me heterophobic or anti-Christian, because I

have special rights that make me untouchable. In fact I can pretty much do and

say whatever I want because I don’t have the same privileges as you, but the

group I belong to is disadvantaged, therefore I have unimpeachable rights.

The

presumption of special rights explains the culture of victimhood. It goes

without saying that individuals or groups can be, and are, the victims of terrible

wrongs, but one has to have been wronged

to be a victim. It is not sufficient to be a member of an identity group. That

said, it’s easy to see the appeal if membership of a group means being treated

in a special way. Who wouldn’t want to join up?

This is what

flummoxes our governing bodies. When considering these demands they can’t see

their way through the argument, because the idea of rights is so convincing and

yet inevitably leads to deadlock. A woman has a right to choose what happens to

her body, but a foetus has a right to life. Male-to-female transgenders have

the right to use women’s toilets, but women have the right to safe spaces. Individuals

have the right to free speech, but people have the right to be protected from

hate speech. Each right of each special group cancels out the opposing right, meaning

that no resolution is possible.

The only

option is to shout the loudest and heap the most abuse on one’s opponents, and

this is where social media come in. Ironically, the tactic often used is to

accuse one’s opponent of being in a certain group: “You’re just an old, white

male, so your views don’t count”. No matter how righteous and intersectional you

feel when tweeting this, it’s a tactic that involves assuming that certain

groups don’t have the same universal rights as others. Surely the danger is

obvious? It’s not so long ago that

“You’re just a young, black male so your views don’t count” seemed just as

incontrovertible.

The idea

behind universal human rights is to stop this historical flip-flopping of

who is currently persona non grata by rejecting special privileges for special

groups. Those framing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948

believed in the existence of “rights that are inherent to all human

beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or

any other status”. They are truly universal, and they impose universal moral

responsibilities for how an individual should behave towards others, unlike special

rights, which encourage an obsession with how others should behave towards an

individual.

On Sunday 15 March Joe Biden announced

during the CNN Democrat debate, "If I'm elected president, my cabinet, my

administration, will look like the country. I commit that I will, in fact, pick

a woman to be my vice president." Fitness for the position, apparently, is

a secondary consideration. This doubtless wins Biden kudos from the left, but Christopher

Hitchens in a 2008 article says it best:

People

who think with their epidermis or their genitalia or their clan are the problem

to begin with. One does not banish this specter by invoking it. If I would not

vote against someone on the grounds of ‘race’ or ‘gender’ alone, then by the

exact same token I would not cast a vote in his or her favor for the identical

reason.

Hitchens died in 2011 and so missed the

worst of the latest obsession with identity politics, but it is worth looking

back at the arguments of this

combative writer. He pointed out

that Martin Luther King argued that colour is irrelevant, not that it is the

defining feature of a person’s identity. The current woke phrase “person of

colour” makes being or not being white the sole intersectional feature, and

while paving the way to weaponising the

phrase “white privilege” has the consequence of lumping together all other

races of the world, as if the Japanese businessman, the Inuit hunter and the Syrian

refugee mother actually share something meaningful in being non-white.

What our governing

bodies need is a decision-making tool that allows for moral debate rather than

cancellation. That tool can be found in the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights. The Declaration states that we all have the same rights, because

we all have the same moral obligations, and this idea needs to be kept foremost

in mind, and implemented. Special rights for special groups – even if apparently morally righteous

based on historical rebalancing and/or a retribution for past sins – are simply immoral in this light. ‘Positive

discrimination’ was always an unfortunate oxymoron, and it was well replaced by

‘affirmative action’, but action needs to be affirmatively directed at whoever needs

it as a suffering human being, not as a member of a special identity group.

This is not

a solution that ends all debates about competing rights. But it does provide a

framework for thinking about some of our most intractable social issues without

peremptorily shutting down one side of the argument.

David Wolcott

Comments

Post a Comment